(Reprinted from HKCER Letters, Vol.58, March/April 2000)

Comprehensive Social Security Assistance

Left to right: Dr. Alan Siu, Professor Nelson Chow, Professor Liu Pak Wai, Mrs. Rachel Cartland, Mr. Robert Rector, and Professor Y.C. Richard Wong

IntroductionComprehensive Social Security Assistance (CSSA) expenditure has been increasing dramatically, recording growth rates of 47.5% in 1996/97 and 32.5% in 1997/1998. In the fiscal year 1998/99 alone, HK$13 billion was spent on CSSA, accounting for 7.8% of HKSAR's recurrent expenditure. With such alarming increases, there is an urgent need to investigate the effectiveness of the CSSA scheme. Can the CSSA scheme restrict cash handouts only for those with no other option? What can be done to promote and encourage self-reliance?

In order to come up with a well-rounded and practical approach for the future of social assistance in Hong Kong, we need to first establish clear objectives as well as learn from our past experience and the experience of other countries. As a contribution to the public debate, the Hong Kong Institute of Economics and Business Strategy and the Hong Kong and Asia-Pacific Economies Research Program of the Chinese University of Hong Kong held a symposium on CSSA on 2 March 2000. This symposium drew together specialists with different perspectives to investigate the effectiveness of our current CSSA system, and explore ways to ensure how the CSSA could better serve the public while making the most effective use of our taxpayers' money.

We are honoured to have the participation of four outstanding professionals contributing to this symposium, providing valuable insights and expertise for Hong Kong's Comprehensive Social Security Assistance Scheme. They are:

Mrs. Rachel Cartland, JP

Assistant Director

Social Welfare Department

HKSAR Government"A More Integrated Approach to CSSA"

Mrs. Cartland is Assistant Director of the Social Welfare Department, taking responsibility for Hong Kong's social security programmes. This challenging job involves analysis of major policy issues, management of almost 1700 staff and 38 field offices. Mrs. Cartland will give an overview of the current CSSA as well as discuss their mission to constantly upgrade service levels including the forthcoming introduction of a HK$225 million re-computerisation programme. Graduated from Oxford University, Mrs. Cartland has more than twenty years of experience in the Administrative Grade of the Hong Kong Government.

Professor Nelson Chow Wing Sun

Dept. of Social Work & Social Administration

The University of Hong Kong"Social Security in Hong Kong - Time for a Revamp?"

The existing CSSA Scheme is both inefficient as a safety-net and ineffective in helping recipients to stand on their own feet. Professor Chow will examine the shortcomings of the current CSSA Scheme as well as propose practical ways to make it to be more efficient and effective. Professor Nelson Chow is Chair Professor of Social Work and Social Administration at The University of Hong Kong. He is a former chairman of the Social Welfare Advisory Committee and the Hong Kong Council of Social Science. Currently he chairs the Mandatory Provident Fund Advisory Committee.

Prof. Liu Pak Wai

Pro-Vice Chancellor & Co-Director of

H.K. Asia-Pacific Economies Research Program

The Chinese University of HK"Financing the CSSA Scheme"

Prof. Liu will explore the reasons for rapid growth in the spending of the comprehensive social assistant scheme. He will examine the trade-offs involved and pinpoint measures for improving the financial aspects of the scheme. Professor Liu holds an A.B. from Princeton University and M.A., Ph.D. from Stanford University. He is Professor of Economics and Pro-Vice-Chancellor of The Chinese University of Hong Kong. He is a member of the Economic Advisory Committee, the Commission on Strategic Development, and the Task Force on Employment.

Mr. Robert Rector

Senior Research Fellow

The Heritage Foundation"Welfare Reform in the U.S."

There are more than 70 major government programs that give aid to targeted low income and "poor" households in the U.S. The welfare programs aid about one fifth of all Americans and cost around 5 percent of US GDP. Mr. Rector is one of the principle architects of the welfare reform legislation that was passed in Washington in 1996. He will talk about the U.S. welfare system, reforms implemented, how well the reforms are working and further measures to improve the system. Mr. Rector holds a B.A. from the College of William and Mary and an M.A. in political science from Johns Hopkins University.

A More Integrated Approach to CSSARachel Cartland

IntroductionToday I am not going to give details of the workings of the Comprehensive Social Security Assistance Scheme (CSSA), but I would focus on a particular aspect that I am interested in, namely, a more integrated approach to CSSA. In the past, CSSA has always been viewed as the special preserve of the social work sector. Obviously our social security system (welfare system in American terms) is dealing with the most vulnerable part of our society, the lower part of the socioeconomic pile. It is natural that the social work way of looking at things should have an important part to play. Our welfare system has literally developed over the recent past from a network of feeding stations handing out rice to the destitute into a really quite complicated cash transfer system. If you are familiar with the British Supplementary Benefits System, you will be able to understand our system quite easily. For obvious historical reasons, our CSSA system is to some extent derived from the British system and also has resemblances with other systems in the same "family": Australia, Canada, New Zealand and to a somewhat lesser extent, the American welfare system. Consequently, recent developments in these systems, debates about welfare dependency etc. have also been of interest and relevance to Hong Kong.

I am delighted to be here today for many reasons but an important reason is that this Symposium reflects a most welcome innovation in looking at social security issues in a context slightly different from that in which they are usually considered, i.e. as a social service examined through the perspective only of social workers.

It would be wrong, of course, to deny the very valid social work interest in our social security schemes. The CSSA is the primary form of monetary assistance to the most financially vulnerable members of the community. It thus has a fundamental role to play in any strategy of poverty alleviation. Financial vulnerability is often accompanied by a multiplicity of other problems which require professional intervention by social workers. As we deal face-to-face with social security applicants and recipients, we should constantly bear in mind relevant social work values, particularly empathy to those who are going through a tough time in their lives.

Increase in CSSA SpendingNonetheless, one might suggest that over the recent past the social welfare viewpoint has become almost a victim of its own success when it comes to social security. The entirely understandable call that social security recipients should not be excluded from the increasing affluence of our community meant that between 1992/93 and 1998/99 CSSA standard rates increased in real terms by at least 20 percent and at the upper end by more than 100 percent. The expenditure on CSSA increased from HK2.4 billion in 1993/94 to over HK13 billion in 1998/99 which represented a four-fold increase in five years. During the early 1990s CSSA expenditure accounted for just 2 percent of Government recurrent expenditure but by 1998/99 that figure was 7.8 percent. Such phenomena are bound to attract the attention of people like those in today's distinguished gathering, i.e. the economists and, indeed, rates of increase like those I have just quoted are bound to raise questions about the long-term affordability of the scheme especially during times of economic recession.

So, we have already recognized that economists with an overall interest in Government's fiscal and expenditure position as a group are now likely to take an interest in CSSA. But there are others too! Another phenomenon that became apparent in the mid-1990s was the steep rise within the CSSA caseload of cases in which the principal applicant was an able-bodied and therefore employable person. Between September 1993 and September 1998 the "unemployed" proportion of the caseload rose steadily from 4 percent to 12 percent and yet this increase did not at all correlate with employment opportunities or the lack of them within the community. For example in 1996/97 the unemployment rate was 2.6 percent while CSSA expenditure increased at a rate of 47.5 percent. In 1997/98, the corresponding figures were 2.5 percent for the unemployment rate and 32.5 percent for the rate of increase in CSSA expenditure. Accordingly, we began to have concerns about the possible emergence of a dependency culture.

Support for Self-relianceAs we studied this phenomenon we began to understand that we needed to integrate our thinking more closely with that of colleagues in the Labour Department, Employees Retraining Board and Education and Manpower Bureau. Discussions with them were an important contribution to the new policy strategies outlined in the report Support for Self-reliance published in December 1998. The basic policy aim was now stated as being to assist the employable in our caseload to become self-reliant and gainfully employed. To achieve this, we have adopted a more proactive approach towards unemployed CSSA recipients with social security staff working with them on individualized job search plans and ensuring a better information flow about resources available through other parts of Government. The results have been little short of spectacular: between 1 June 1999 when the scheme was implemented and the end of December 1999 the "unemployed" component of the CSSA caseload registered a 13 percent drop.

To maintain the momentum, however, we have to deepen and broaden this integrated approach. An important next step will be to strengthen our relationships with non-governmental organizations. We would like to work more closely in partnership with them on strategies to help move those of our CSSA recipients with very entrenched problems back into the work force. These entrenched problems may be no more than simply those which arise from being a long-term CSSA recipient. In common with other developed social security systems we have found that a longer period of CSSA dependency correlates with difficulty in leaving the system.

Ideally, we would also like to find ways and means to reach out to the business community and to bring them into a partnership to mobilize the human capital that our recipients represent. It seems inherently illogical that while our unemployed caseload remains at some 28,000, Hong Kong employers are asking the Labour Department for permission to bring in more than 1,000 workers to undertake simple, low skill jobs. More ambitiously, we need to work together, Government and the community, to find better ways and means not just to mobilize unemployed CSSA recipients but to invest in them so that their working capacity can be enriched and the barriers that currently keep them from fully participating in the economic life of society be overcome.

Investment in Human CapitalSo, we have identified social work and economics broadly as two academic disciplines likely to have a very strong interest in the CSSA. It would be nice if there was some sort of middle ground in which these two disciplines met. The Second Asian Regional Conference on Social Security was held in Hong Kong this January. The keynote speaker, Professor James Midgley of the University of Berkeley in California is Dean of the social work school but an important theme in his speech was that when it came to the study of social security, economic realities can no longer be ignored. I heard other participants at the conference expressing their appreciation of Professor Nelson Chow's attitude when he sounded the same note in his approach to the Mandatory Provident Fund. The challenge that Professor Midgley left us with was to try and think of social security as "investment in people", or in "human capital" if you like a more "scientific" and less "emotional" term. Here, it seems to me there may be particularly fruitful areas for the benefits of a more integrated approach as we build on Support for Self-reliance and, for example, try to mobilize insights from the field of labour economics.

Managing CSSAFinally, let me briefly mention one more academic discipline which currently seems to take little interest in social security but perhaps could do so with benefit and that is the field of management studies. Just as formerly it sometimes seemed to be assumed that with the right degree of willingness on the part of Government almost unlimited amounts of money could be made available for social security, I feel that nowadays the complexity of managing a social security system is sometimes under-estimated. Hong Kong's social security system already, of course, makes use of information technology and will do so much more from this October when we will be adopting a fully on-line approach. It is a constant management challenge for us to operate systems which are efficient and can be mastered by staff without undue difficulty and to support staff to find the right point of balance between stringent assessment of eligibility for benefits and understanding of the vulnerabilities of the customers that they serve.

Experience here and, even more so, looking at what has happened in some overseas social security systems convinces us that a simple yet efficient system is absolutely vital in the best interests of our needy customers as well as the overall good of Government financial management. This is a dimension to which, I sometimes feel, insufficient attention is paid when innovative social security proposals are put forward.

Concluding RemarkAt symposia or conferences, it is usually the role of the Government representative to be lectured at as well as to give a lecture. That is something that is entirely right and proper since we need constant input from a variety of sources to allow us, as far as possible, to get our programmes on the right track and to keep them there. I am therefore looking forward to taking away from today's programme a wealth of insights and, ideally, seeing the foundations laid for a whole range of more fruitful, integrated co-operation with various sectors and viewpoints within the community.

Social Security in Hong Kong - Time for a Revamp?Nelson Chow Wing Sun

Introduction

Just now Mrs. Cartland talked about the changing CSSA scheme, and I am going to share with you my understanding of the system. The CSSA scheme has become so complex that we have to do something in order to make it more efficient and also more effective as a safety net. Of course, I think it is true that there is always room for improvement, no matter how efficient and effective the scheme is at a given point in time. Things do change over time, and as the system becomes too complex, we have to do something to make it better.

The CSSA scheme started in 1971. Since then we had a number of major revamps of the system. A green paper on welfare was published in 1977, and a white paper in 1991. The most important change was the introduction of a number of supplements, like old age, sickness and disability, on top of the basic subsistence support. The supplements are meant to take care of the special needs or additional needs of the recipients. Another major change was in 1981 when the scale rate was revised upward. Then in 1992 there was a review of the system and the name of scheme was changed from "Public Assistance" to "Comprehensive Social Security Assistance" (CSSA). We now have 8 years of experience with the current system. It is time for us to look at it again.

Just now, Mrs. Cartland talked about the rapid increase in CSSA expenditures and the rise in the number of cases in the 1990s. I remember in 1991/1992, the expenditure in the PA scheme did not exceed one billion dollars. We have seen a 12-time increase in CSSA spending in the past decade. Besides the rapid increase in expenditure, there was also a great change in the composition of CSSA recipients. Before 1995, the majority of the recipients were elderly people. The elderly plus disabled persons accounted for over 80 percent of the recipients. Just a few of the recipients were unemployed persons and what we now call "single-parent families". In the last few years things have changed rapidly. The scheme now provides support for recipients with very diverse needs and problems.

The Mandatory Provident Fund (MPF) will start by the end of this year. Even with the MPF, the CSSA spending in support of the aged poor would not decrease. I suppose about 10-15 percent of the elderly, now and in the future, will not have enough money to support themselves. For example, those just earning $4,000 would not have to make a contribution themselves although their employers have to make contribution for them. Those who are earning low wages, say between $6,000 to $7,000, and do not have a long enough time to make contributions to the MPF, will in the end call for CSSA. So I do not think our CSSA will disappear in the future. Even with the MPF, about 10-15 percent of the elderly will still be in need of assistance. So in publicizing the MPF, we have to be aware that MPF will not be a protection for all. The retirement protection system will comprise three components: one is MPF, one is CSSA, and the other is personal savings which will be an important component for most retirees. Do not think that once we have the MPF, we are going to do away the CSSA for the aged poor.

Changing ObjectivesThe CSSA started as a scheme to provide subsistence living for the non-working poor, and has evolved over the past 30 years into a complex system. It now provides support for recipients with diverse needs and problems. Specifically, the scheme provides basic pension for the aged poor, unemployment assistance for unemployed workers with insufficient means, income supplements for families earning low incomes, financial relief for single-parent families, and support for persons suffering from illness or disability. Although some people are still urging for an unemployment assistance scheme for all, I do not know whether the government will do it. I am not going to comment on this idea here, but the CSSA already provides assistance to the unemployed. The number of unemployed workers on CSSA increased very rapidly. As Mrs. Cartland just mentioned, we have seen a drop in the unemployed caseload last year. I think the unemployment part of the CSSA is going to stay to provide a safety net. There are economic ups and downs. Maybe in the next year or so, we will see an improvement in the unemployment rate. But somehow a society like Hong Kong will always have a certain number of people who for various reasons are unemployed and cannot support themselves. I think the CSSA is going to be there to help this group of people.

The CSSA provides income supplement for those families who are earning very low income. The point we have to watch is the gap between the rich and the poor in Hong Kong. There are a substantial number of workers who are not highly educated and have very low skills. They do not earn enough to support themselves and their families. They need support, not full support but at least partial support, from the CSSA scheme.

The CSSA provides financial help for single parent families. The number of single parent families receiving CSSA has also increased rapidly in the last few years. The number of cases is around 25,000 now. This is partly because of the increase in divorce rate, and partly because of a well-known social phenomenon. A sizable number of men from Hong Kong got married in Mainland China. Their children are here with them, while their wives are still in the Mainland. More and more of this kind of pseudo single-parent families are receiving CSSA. The father has to take care of two or three children, while his wife is in the Mainland. Very often, he is earning very low income or even unemployed. We all understand that there are many children and wives in the Mainland waiting to come to Hong Kong. It will take a few more years to change the situation. I think quite a number of these families will be in need of CSSA.

Other people who are in need of CSSA are those suffering from illness or disability. The scheme also serves as a last resort for all those requiring financial assistance.

A Complex SystemAll I want to say is that CSSA is no longer a simple scheme to provide a single safety net for all who are poor and unable to maintain a basic living standard. We must recognize the complexity of the existing CSSA as a measure to relieve poverty. The present administrative structure responsible for running CSSA is no longer effective in meeting the needs of the recipients nor adequate in rendering the help required.

I am not saying that those working in the social security field units are not efficient. They really have to work very hard especially in the past couple of years. They face a lot of difficulties in coping with the increasing caseload and the complexity of the scheme. I would like to point out two things related to administration. The first is the training of the social security officers who are now responsible for running the whole system. They are basically trained just to make the assessment because it is a means-tested scheme, and to treat all the applicants fairly as far as possible. In other wards, once meeting the requirements, the applicants are able to get the benefits as a matter of right. I think basically they are asked to do this. But when you look at the reasons why people are applying for CSSA, the officers are now dealing with all sorts of problems. It is not just simple financial assistance. When the unemployed come for assistance, their problem is not just short of money for basic living. They are unable to find jobs to match their skills. CSSA applicants have problems besides financial needs. The staff are asked to run the scheme, but they are not equipped with the skills to deal with the myriad problems of the applicants. The inadequate training affects the efficiency and the effectiveness of the scheme.

The scheme started as a simple one, but as I have mentioned, the situation has changed over the years. More and more discretionary items have been added to the scheme. I do not think every worker working in the field units can remember all the items. I have a chance to look at the manual and it is so thick. Sometimes the field workers might miss one or two, and sometimes they might not be able to judge whether an applicant is really eligible for a particular benefit or not. The scheme and the procedure are so complicated. The system is not simple to administer.

The other point is that recipients are poor for a number of reasons and financial assistance should form only a part of the efforts to help them live out of poverty. If you try to help them, you do not want to make them rely on CSSA forever. You have to understand why they have to apply for assistance. I want to stress that they do not merely need money. They have other problems to deal with. Cooperation with other organizations, both public and private, is required to help them in tackling their specific needs. In other words, if you want to do something to help the recipients, and not just give them money, it is not going to be an easy task at all.

Suggestions for ReformMy suggestions aim at making the system more tidy. The CSSA scheme should adopt a "categorical" approach by dividing the recipients into categories, each with its own scale rate, eligibility criteria, conditions for assistance and kinds of help offered. Field workers will then get a clearer idea of what to do with the applicants. The applicants will in turn have a better idea of their benefits.

The important thing is that each category has its own scale rate. This will avoid a lot of difficulties of the current system. We must understand that different people have different needs. We must recognize that some people do not merely need money. Each category of recipients must have its own scale rate and eligibility criteria. We must change the current system. I think we must be very clear in order to avoid any misunderstanding and misconception about the CSSA system.

I am not going to advocate drastic changes, but we have to make the system more efficient and more effective. I suggest the following categories:

1. Old Age Assistance

The financial needs of the elderly should be considered together with their needs for housing and health care. Elderly people do not just need money. Housing is important for them and health care is even more important. I have met a lot of elderly people living on the CSSA. No one told me that they did not have enough to eat. They were worried about health care when they became sick. This is why they have to save out of the money received from CSSA. So if we want to make the system more efficient in helping the elderly, the Social Welfare Department must work together with other departments responsible for housing and health care.

2. Unemployment Assistance

The unemployed recipients should be taken as a group. I do not think the Social Welfare Department is the best department to help the unemployed workers to go back to work. The field workers can assess the financial needs of the applicants, but are not well suited to find jobs for them. The Labour Department must play a role in getting the unemployed CSSA recipients back to work.

3. Families with Dependent Children Assistance

Social workers should be involved in helping these families. We know that single parent families need more than financial assistance. Their need for family services is also very great. We have to cater for the special needs of the children.

4. Sickness and Disablement Assistance

The task of rehabilitating the sick and the disabled is more important than just giving them financial support.

Concluding RemarksA categorical approach will make the CSSA more effective. Applicants will know exactly what to expect from the system, and the field workers will know what kind of assistance to provide. We want to get an unemployed CSSA recipient back to work as quickly as possible, but we would not expect an elderly recipient to go out and search for a job.

It is time to revamp the entire CSSA scheme to make it more a measure to help the poor to help themselves. We must go beyond the objective to "assist the vulnerable members of the society with financial or material assistance", as stated in the 1991 White Paper on social welfare. We must try to achieve more by dealing with the reasons why they are on CSSA, instead of just giving them financial and material support.

Financing the CSSA SchemeLiu Pak Wai

IntroductionThere are three parts in my presentation. First I will discuss briefly about the fiscal implications of the CSSA scheme. Then I will try to explain why CSSA payments increased sharply after 1993. Finally, I will present some tentative proposals to contain cost, and I emphasize the tentative nature of my proposals.

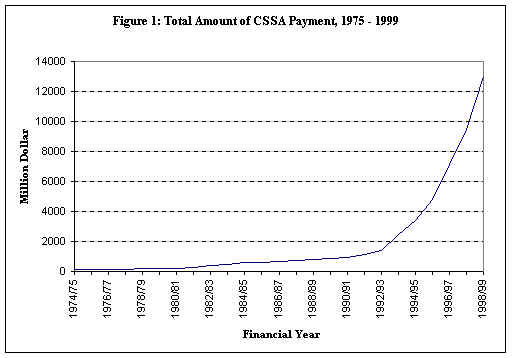

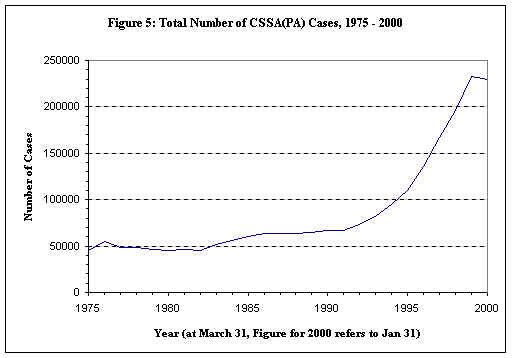

Fiscal ImplicationsFigure 1 shows that the CSSA total spending from 1975 (Public Assistance (PA) before 1993) up to now. In 1992/1993, when the spending started to increase exponentially, it was around 1.4 billion. In 1999 it was 13 billion, a 9-fold increase in 7 years.

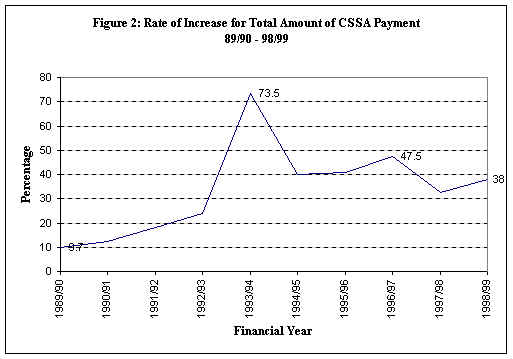

The annual rate of increase of the CSSA spending starting to rise sharply in 92/93 and went up to 73.5 percent in 1993/94 (Figure 2). Even though it dropped to around 40 percent in the following year, it is still a huge rate of increase. Since then the rate has fluctuated around the same level. It was still 38 percent in the last fiscal year.

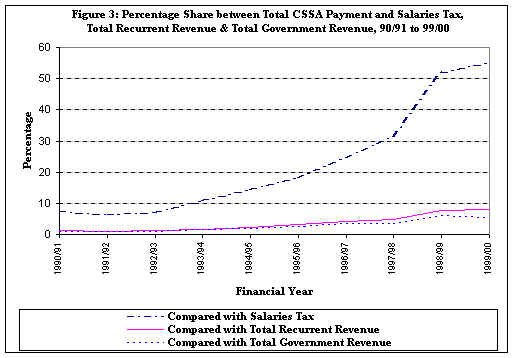

Figure 3 illustrates the financial implications of the CSSA scheme. The ratio of CSSA spending to salaries tax revenue increased rapidly over the years. By now well over 50 percent of Hong Kong's salaries tax is used to finance the CSSA scheme. If we use the total government revenue as a yardstick, 8 percent of the total government revenue is spent on CSSA.

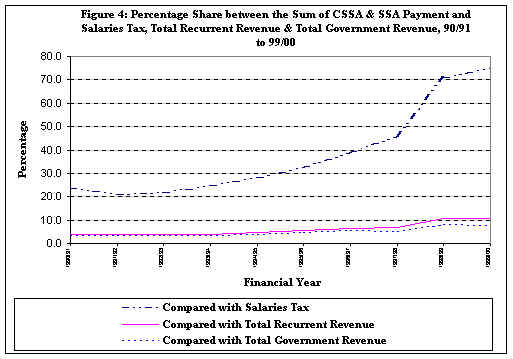

If we add in the Social Security Allowance (SSA) which is the non means-tested part of the welfare program, then the percentage goes up to 75 percent (Figure 4). If we further include costs of the welfare system, like staff costs and the costs of all the subvented programmes, then the total welfare payment will exceed the total salaries tax. The salaries tax is not able to pay for the welfare expenditure in Hong Kong.

Sharp Increase After 1993There are two components contributing to the sharp increase in CSSA spending after 1993, the number of recipients and the average amount of payment to each recipient. These two components are related. Let us first look at the number of recipients. Figure 5 shows that the number of CSSA cases had been relatively stable from 1975 up to the early 1990s. It increased sharply around 1993, from 80,000 cases to about 230,000 cases now. There has been a slight drop since the end of 1999. Even though the number of CSSA cases increased by threefold from 1992 to 1999, it cannot fully account for the 9-fold increase in CSSA spending. The other component that contributes to the large increase is the huge increase in the average CSSA payment.

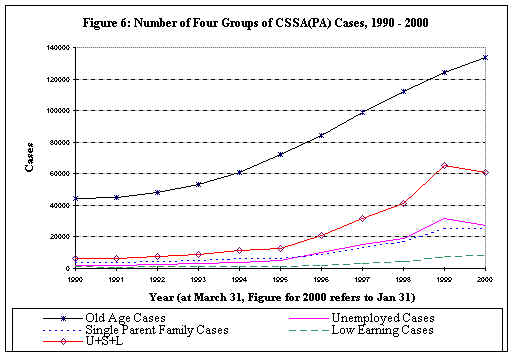

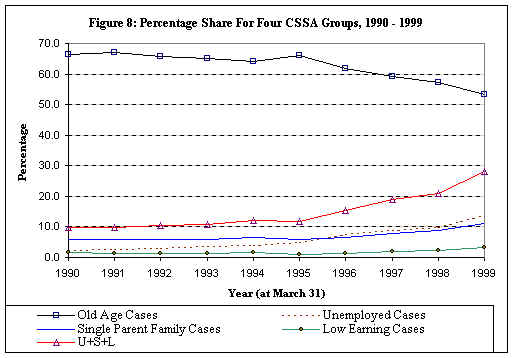

Before turning to the average payment, let us look at the number of CSSA cases more closely. Figure 6 shows the four major components from 1990 to 2000, old age, single parent family, unemployed and low earnings cases. Except for a drop in the number of unemployed cases between 1999 and 2000, all four components show an increase over the years, but at different rates. Figure 7 shows the rates of increase of CSSA cases. The sharpest increase is in the number of unemployed cases which went up to 85 percent in the year 1995/1996 from 35 percent the year before. There was also a sharp rise in the number of single-parent cases. The number of elderly cases also increased over time but the rates of increase were more moderate. As a result of the differential rates of increase, the ratio of old age cases dropped to half of the total, while the other three components became relatively more important in proportion (Figure 8).

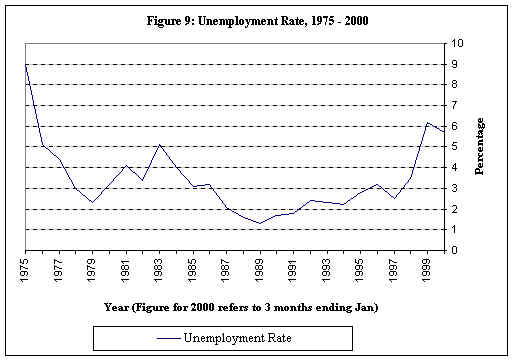

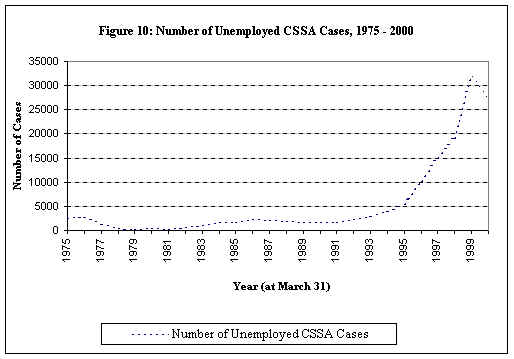

The rapid increase in the number of unemployed CSSA cases since 1993 has nothing to do with the unemployment rate. As a matter of fact when unemployed CSSA cases increased rapidly, in the mid 1990s, there was essentially full employment in Hong Kong. Figure 9 shows the unemployment rates in the past 25 years which show three peaks: 9 percent in 1975, 5 percent in 1983 and 6 percent in 1999. Matching the profile of unemployment rate (Figure 9) with the number of unemployed CSSA cases (Figure 10) shows that there is no relation between the two profiles. The number of unemployed CSSA cases simply went up after 1993 when the labour market was still rather tight, whereas in the previous two peak periods of unemployment (1975 and 1983), the number of CSSA cases was moderate.

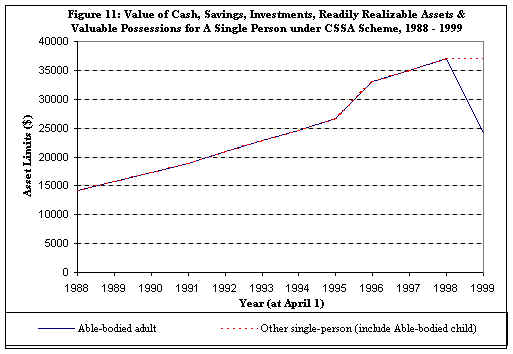

How can we explain the increase in the number of unemployed CSSA cases if the underlying unemployment rate has an insignificant impact? Could the increase in the number of unemployed CSSA cases be accounted for by the relaxation of the asset limits of the eligibility requirement for receiving unemployed CSSA? Figure 11 shows that the asset limit for single able-bodied adults has been raised steadily and moderately over time. In 1995 the asset limit was increased somewhat faster than the trend. The increase is partly to offset the effect of tightening of the eligibility requirement in that year; henceforth CSSA recipients were no longer allowed to receive rental income from their property. There has been a reduction in the asset limits for single able-bodied adults after the review in June 1999. Over the years, the asset limits have basically been increased gradually to take into account inflation. Hence, the large increase in the number of unemployed cases since 1993 cannot be due to changes in asset limits which expand the number of eligible persons.

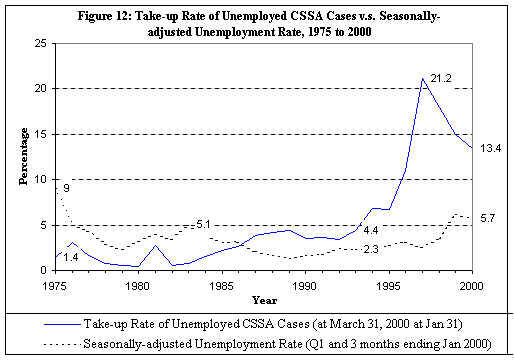

Figure 12 shows the take-up rate of unemployed CSSA cases. In the 80s and early 90s, the take-up rate is one to three percent, that is out of one hundred unemployed persons, only one to three persons would receive CSSA. The take-up rate shot up to 21 percent in 1997 which incidentally was a year of full employment. (The figure refers to the end of March in 1997 before the financial crisis.) In that year one out of five unemployed received CSSA, whereas historically only 3 out of 100 unemployed workers were recipients. Over time, there has not been significant changes in eligibility requirements that could account for this large increase in the take-up rate. Something drastic has obviously happened.

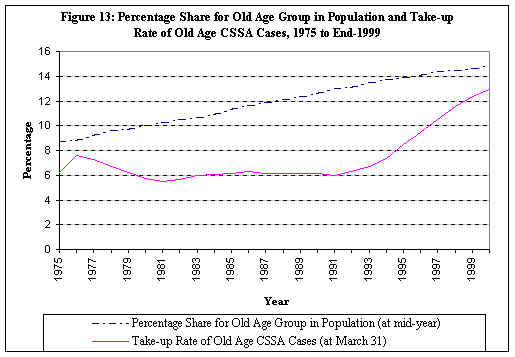

In fact the same pattern shows up in the elderly cases even though it is not as dramatic. The dotted line in Figure 13 shows the percentage of the population that is aged 60 or above from 1975 to 1999. It clearly shows that the population is aging. The solid line shows the take-up rate of old age CSSA cases. The take-up rate had been stable at around 6 percent in the 1980's. It started to increase rapidly after 1993 to reach around 13 percent in 1999.

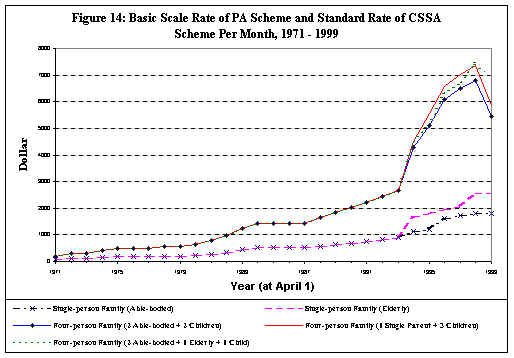

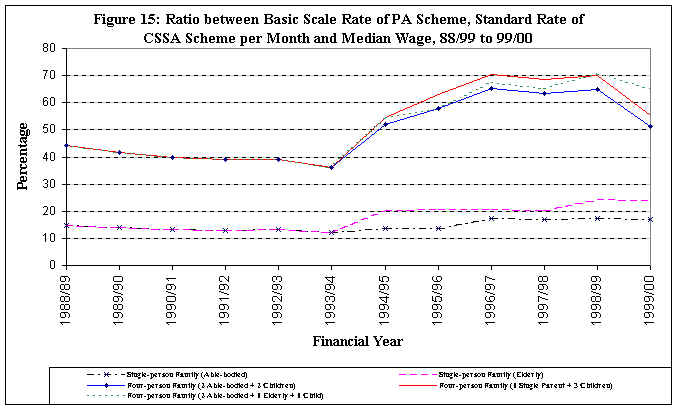

It should be stressed that among the potentially eligible recipients -- the elderly and the unemployed, the take-up rate has increased sharply. What caused such a dramatic increase in the take-up rate? Figure 14 reveals the answer. There was a substantial increase in the CSSA standard rate in 1993, and again in 1996. (Separate standard rate of payment applies to different categories of recipients, such as single person able-bodied, elderly, disabled, etc.) It shows that the standard rates of 5 representative recipient families increased sharply in 1993. Figure 15 uses the median wage as a yardstick for comparison. The standard rate of a 4-person family went up steadily after 1993 and reached 70 percent of the median wage in 1996. Before 1993 it had been around 40 percent of the median wage. For a single-person family, the pattern is similar but less dramatic. The standard rate for a single-person family is around 25 percent of the median wage.

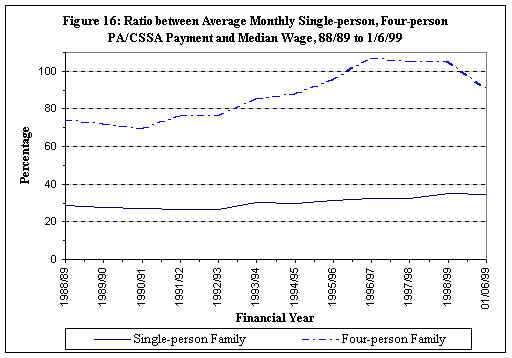

It should be noted that besides the standard rate, CSSA recipients are eligible for special allowances, like rental assistance, tuition fee and lunch subsidy for school children, dental reimbursement etc. The total amount received by a CSSA family includes the standard rate payment and the special allowances. Figure 16 shows the average monthly total payment for two categories of recipient families, as a percentage of the median wage. While the standard rate for a four-person family is around 70 percent of the median wage, the average actual amount which includes the special allowances for a four-person family is above 100 percent. In other words a 4-person-family on the average is receiving CSSA payment that is more than the income of half of the working population. The CSSA family members do not work and yet they are better off than a family of four whose head is working and receiving the median wage. This comparison should give an indication why there has been such a sharp increase in the number of CSSA cases starting from 1993. What happened in 1993 is that the Hong Kong Government increased the CSSA payment substantially, triggering a sharp increase in the take-up rate. Before 1993 a large number of people who were eligible for CSSA chose not to apply for the scheme because the payment was not that attractive, and they had other means to cope. Since 1993, due to the large increase in the payment rate, CSSA became very attractive. Eligible persons responded to the economic incentive and found it worthwhile to apply for the scheme.

The increase in the take-up rate of the elderly can be interpreted as a response to the increase in CSSA payment rate. Before 1993, many elderly people eligible for CSSA did not join the scheme and the take-up rate was low. They were either supported by their children or they had other means to cope. After the sharp increase in the CSSA payment in 1993, the children might tell their parents to apply for CSSA because the payment became more attractive, and they might withdraw their financial support for their elderly parents. As a result, there was a sharp increase in the take-up rate. The government was substituting CSSA support for family support. The same interpretation can be applied also to the unemployed. After the sharp increase in the standard rate, more of the unemployed found it attractive to apply for the CSSA rather than to look for a job.

The increase in the standard rate may cause an increase in the number of fraudulent cases, but the sharp increase in the number of CSSA cases cannot possibly be explained by fraud. Fraudulent cases could only account for a very small portion of the increase. The sharp increase in CSSA cases also cannot be explained by social workers working harder to help eligible persons to apply for CSSA. There is no reason to believe that social workers suddenly worked very much harder in 1993, the year when the number of CSSA cases took off. We can only conclude that the rapid increase in the number of CSSA cases is a response to the large increase in the CSSA payment after 1993. A large number of eligible persons, formerly foregoing CSSA and coping with other means, are now on CSSA. CSSA recipients respond to economic incentives just like everybody else.

Containing costsWhat can be done to contain costs? Several proposals are worth considering. Experience indicates that when the average CSSA payment was around 80 percent of the median wage in the late 1980s, the take-up rate was stable. However, when the payment was increased to above 100 percent of the median wage, there was a sharp increase in the take-up rate. Total payment and take-up rate are empirically related. To stabilize the take-up rate at a manageable level, CSSA payment should be linked to the median wage at, say, the 80 percent level.

Another possible measure to contain costs is to take into account a CSSA recipient's accrued benefits of the mandatory provident fund (MPF) in calculating CSSA payment. Consider a person earning $10,000 a month. The combined monthly MPF contribution from the employer and the employee will be $1,000, After 3 years, the MPF balance of this employed person will be $36,000, plus investment returns. This amount exceeds the current CSSA asset limit for a single person. If MPF accrued benefits are counted as part of asset, he will not be eligible for CSSA if he becomes unemployed subsequently. How can this unemployed person survive without any current income? We should consider amending the MPF Ordinance to allow unemployed workers to draw on their own MPF accrued benefits while they are unemployed. Basically it is asking the unemployed to internalize their welfare benefits as much as possible before resorting to public assistance. Unemployed persons should first make use of their own resources including their MPF accrued benefits before being supported by public money.

But if unemployed persons run down their MPF balance, how are they going to support themselves when they retire? There are two possibilities. One possibility is that their unemployment is short-term. After a short period of unemployment, they will find a job and start to accumulate their MPF balances again. Young workers have 20 to 30 years to accumulate for their retirement. Short spells of unemployment during their work career will not hurt their long-term retirement protection by much. The government will save a lot of money because it does not have to pay CSSA for these short unemployed spells. The second possibility is that their unemployment turns out to be long-term or they are approaching retirement and there is no time to accumulate the MPF benefits. If that is the case, their MPF balance will be run down and they will become eligible for CSSA. In any case they will have to be supported by CSSA after retirement. CSSA will continue to offer a safety net. To summarize, allowing unemployed workers to draw on their MPF balance before applying for CSSA will save public money, but this will require amending the MPF Ordinance.

As for the retirees, it is logical to count their accrued MPF benefits as part of their assets. The asset limit for old age CSSA should take into account MPF balances.

The third proposal is to provide greater incentive for work. The current CSSA scheme rules allow about $1,000 as disregarded income if the CSSA recipients work. The disregarded income can be increased so that the more they work, the more income they will get. CSSA recipients should be allowed to keep more of their earned income while receiving partial CSSA support up to a cutoff point when they will be on their own. More thought should be given to build in greater incentive for CSSA recipients to work.

The fourth point deals with single-parent families. The Government has to provide more child care and other support, and to help divorced women collect court mandated alimony from their ex-husbands. This will reduce their reliance on CSSA.

These proposals are tentative. The review of the CSSA scheme by the government in June 1999 is a step in the right direction. The standard rate for able-bodied recipients was reduced by about 10 percent to make it less attractive. A self-reliance requirement was introduced to make it more costly for the unemployed recipients to remain on CSSA. Since the review, there has been a decrease in the number of CSSA cases. It is still too early to say whether these factors can account for the reduction. We have to monitor the number of unemployed CSSA cases further before we can be sure of the effectiveness of the measures introduced in the review. The initial signs are, however, encouraging.

Welfare Reform in the U.S.

Robert Rector

IntroductionI think Hong Kong is very fortunate in the sense that you have not really created a British welfare system. As you look across the world, almost all the developed nations now recognize that in most of the Post-WorldWar period, their welfare systems have been bad with very counter-productive results. What I hope to do today is to suggest ways that you can avoid making the same set of mistakes that were made in the U.S. and other countries. Unless your view of development is that you just want to emulate everything that most developed countries have done in the past, including every disastrous policy that they adopted, then you ought to go ahead to have more welfare, more permissiveness, more handout. You'll make a very miserable class of people by doing that. But then you will be in good company because the U.S. did it, Britain did it, France did it and so forth. I do not think that is exactly the way you want to go.

1996 ReformIn 1996 the US began a rather extensive reform of our welfare system. We started by both parties within our system acknowledging that welfare was bankrupt; it was morally corrupt; it was destructive of the poor. I cannot emphasize it too much. Both parties, the liberal and the conservative, recognized that welfare has desperately failed in the U.S. Beginning with the War on Poverty, we generated one social catastrophe one after another. The most striking of which is that 70 percent of the African American children in the U.S. are now born outside the wedlock. All that directly coincided with the welfare system that we put in place in the U.S.

We started a reform based on the principle that welfare should never be a one-way handout. Dependence is harmful to recipients. A community with a climate of dependence, of receiving something without giving, is a community that is largely unlivable. You are destroying the very people that you are trying to help when you do that.

We decided that we would abandon or try to change the system that would reward parents from having children without marriage. We would abandon the permissive system of simply looking at needs and handing out cash. Based on the idea that everyone in society has something useful to contribute, welfare not only should be but also must be a system of mutual reciprocal responsibility. We do not want to abandon anyone who is in need, but we can insist upon and demand upon constructive behavior on the part of the recipients. This can be done by demanding the recipients to take steps to help themselves, rather than saying the more dysfunctional things you are doing in life. The less you are working, the more children you have outside wedlock, the more you are failing in school, the more stuff we are going to give you. This has been the way conventional welfare had worked before the reform. We had generated with our welfare system populations of dependence. Starting with populations that had stable marriage structure and strong work ethics, over several generations, we created new communities where large cohorts of people were seemingly incapable of working, and where it would be hard to find examples of stable marriages. This was a horrible situation. And we knew that we had to change the system. Instead of rewarding people for taking self-destructive actions in their lives, we would begin to reward them for taking constructive steps to participate in society.

Workfare in WisconsinIn the mid-1990s, the states in the U.S. began significant reform of their welfare systems. The reform process was accelerated by the passage of national reform in 1996. As a result, there has been an unprecedented drop in the welfare caseload, which has declined by some 50 percent from its peak level in March 1994. Wisconsin is the most successful story showing that serious workfare is highly successful in breaking the debilitating habit of dependence. Before the reform, there were more than 100,000 families on welfare in the state of Wisconsin. Reform started in 1994/95 when most recipients were required to undertake an organized job search immediately before and after enrolling in welfare. The result has been spectacular. The caseload dropped by 90 percent to around 7,000 families. The remaining 7,000 cases are mainly African American mothers located in the inner cities who have the most profound social problems. But even for this group, the caseload has dropped by 75 percent. And the 7,000 families are all performing community service work or engaging in full-time constructive work, mostly in shelter workshops. As the caseload dropped, the poverty rate was cut in half.

How does the Wisconsin system work? It's very simple. When someone comes in and says that "I need welfare, I don't have a job and I have children dependent on me." We would say we would help you, but let us first tell you what you need to do to help yourself. First of all, you will have to spend 9 days in an employment center, 5 to 6 hours a day. We will teach you how to find a job and how to do an interview. We will try to see what skills you have. And do not miss a day. If you miss a day without an excuse, there will be no welfare for you. And then you are going to search for a job. You go to the office which has job offers posted on the board. You are going to see if there is a job for which you can get an interview. You can go for the interview, but after that you have to get back to the office within 2 hours. We are going to supervise you every minute. And if you still cannot find a job, we have phone books and phones hanging around. You can seek in the phone books until you can get a job. And that is what you are going to do for the whole day long until you can get a job. And you are going to do that for 3 weeks. If you, at the end, still cannot get a job, that is ok! You are going to do community service work, like sweeping leaves in the park or cleaning toilets in hospitals, and you are going to do it thirty hours a week. We will assist you, but you are going to contribute back to society. You know what happened? They all get jobs! Of course everyone has something better to do than sweeping leaves. After finding out that they have to do community work, 60 percent of the applicants would just walk out and say they do not need welfare.

The work requirement acts as a gatekeeper. The first thing you have to do in a welfare system is to somehow separate two groups of people. One group of people really need assistance, and another, a larger group of people, do not really need welfare. They simply search for a free handout. How do you separate them? Just ask them to work for their assistance, and you will know who really need help. When 90 percent of the people leave the welfare system, you can give more resources and attention to the smaller number of people left in the system. The work requirement has to be imposed at the very front door. Welfare is not about giving you something for nothing, but helping you get back to the mainstream of society. You have to look for a job day after day in a supervised manner from 9 o'clock in the morning, attending interviews and writing resumes in the evening. Searching for a job becomes much like doing a job. In fact searching for a job over and over again really pushes people into getting real paid jobs. Just asking them to go out to find a job without supervision is not effective.

Benefit levelsThe benefit you are going to pay has to be relative to the wage that the recipient is going to get in the real world. If you give a benefit package that is higher than what they are going to get in the real world, they will most likely stay in the welfare system. It is really a simple basic economic idea. The welfare package in the U.S. weighs in US$ 15,000 a year. If you do not have to do anything to get the benefit, there would be more people joining the system. Once the rule is established that welfare benefits must be earned, the attractiveness of welfare would dwindle, and the number of people entering or remaining on welfare would shrink dramatically.

Based on the experience of the U.S., the higher the benefits that you pay out in welfare, the more negative side effects you will have. There are 50 states in the U.S., and each state has different welfare benefits. This allows us to use sophisticated statistical techniques to find out the effects of changing welfare benefits. We have found that a 10 percent increase in the benefit level is correlated with a 15 percent in welfare enrollment. This is not a surprising result, and is based on detailed analyses of data collected over a 25-year period. Another finding which may not be relevant to Hong Kong, but you should better watch out, is that a 20 percent increase in benefit level is correlated with an 8 percent increase in out-of-wedlock births across the entire U.S. One final example that I want to give is the Seattle-Denver income maintenance program. We found in this control experiment that for every additional dollar that we gave in higher welfare benefit, we had a reduction in work effort and earnings of 80 cents. The more money we gave to welfare recipients, the less they would work so that for each additional dollar that we gave them, they would only have an increase of 20 cents in net income.

A lot of people think that welfare dependence is driven by the economy. This is absolutely not true in the U.S. There is very little link up between welfare enrollment and the state of the economy. The determining factor for the number of people on welfare is how tough or how permissive the system is. If you were letting people on easily, without requiring them to do anything, you would have a large number of people on welfare. If you are saying we will only let you on if you take constructive steps for your life, the number of people entering will drop dramatically.

Unwed MothersFinally, I want to talk about something that is very important. In 1965, 7 percent of children in the U.S. were born illegitimate. Today 32 percent of American children are born outside the marriage. The collapse of marriage among blacks has been particularly disturbing. At the outset of World War II, the illegitimate birth rate among this group was slightly less than 19 percent. Between 1955 and 1965, it rose slowly from 22 percent to 28 percent. Beginning in the late 1960s, however, the rate of black illegitimate births skyrocketed, reaching 49 percent in 1975 and 70 percent in 1995.

Federal and state governments currently spend roughly 150 billion per year subsidizing single parents and only 150 million to reduce illegitimacy and increase marriage. Consequently, the conventional welfare system has all but destroyed family structure in low-income communities across the U.S. Welfare establishes strong financial disincentives that effectively block the formation of intact two-parent families.

Children born out of wedlock are prone to take part in criminal activities. Studies have shown that they are 22 times more likely to end up in juvenile courts than children in two-parent families. Many of our inner cities are unsafe, and the welfare system is responsible for this deplorable state of affair.

You should be aware of this problem and take steps to prevent it from happening. Welfare payment should not be too generous to unmarried mothers. The thing we have to do is to preserve the institution of marriage. The welfare system should not act as an encouragement to subsidize divorce. It is a stupid idea that we have to pay people not to work and pay people not to get married. This is hard on the taxpayers as well as very hard on the poor themselves. The right way is to draw on their strength, to reward them for taking charge of their lives, but not to indulge them for every mistake that they make.