(Reprinted from HKCER Letters, Vol.61, September/October 2000)

Personnel Economics and

Economic Approaches to IncentivesEdward P. Lazear

"Personnel Economics" is the field that uses incentive devices and economic analyses to think about human resources issues. It does not take the traditional sociological, industrial or psychological human resources approach. Rather, personnel economics proceeds from the assumption that worker turnover and incentives, pension planning and retirement patterns, staff options and their retention effect - to name just three typical human resource concerns - are inherently economic issues which economists can address from a position of comparative advantage.

Incentives & Productivity

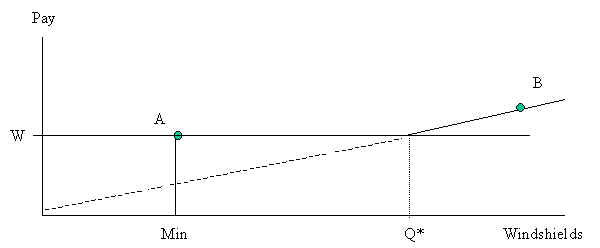

I recently made a study of a company called Safelite Glass, the largest automobile windshield company in the United States. Safelite, with the goal of providing their workers with incentives to produce extra output, was changing their wage system from an hourly-rate to a piece-rate system based on the number of windshields installed. The outcome illustrates very clearly the importance that the choice of compensation scheme has in determining a firm's profitability. It is just as important as any strategic decision a company makes. Figure 1 shows us how the two very different pay schemes affected production. The original pay situation at Safelite, a consistent hourly wage, is represented by line "W". It is flat and perpendicular to the Pay-axis. The reason is, under the old pay system, no matter how many windshields a worker produced, his pay remained the same. The worker was being paid by the hour, not by the windshield. There is a line labeled "Min" in Figure 1. "Min" indicates a cut-off point under Safelite's hourly-wage system: it defines the minimal level of output. If the worker installed fewer than the minimal number of windshields, the worker got fired. In effect, his wage fell to zero. Alternatively, that same worker has the option of producing just the minimum amount. By doing that, he would both keep his job and collect the same pay as a more productive worker. Presented with that compensation scheme, that is exactly what the workers did: they produced exactly the minimum amount, took their wages, and went home. To motivate their workers, Safelite decided to put them on a piece-rate wage system.

The union initially opposed the introduction of a piece-rate system. Unions do not like situations that create heterogeneous outcomes among the workers. However, the union did accept piece rates with an earnings floor; that is, no worker would get less under the piece rate system than he would have under the hourly system. The workers were getting US$88 a day. If they made less than $88 a day on piece-rates, they would still be paid $88. If they made more, they would get a higher amount.

So, again in Figure 1, you see various outcomes. Some workers are content to stay at point A, $88 a day. At point B they would make more money, but have to increase their output from 2 to 5 windshields a day. Some workers do not think it is worth it. On another hand, some workers may say, "I'm at work anyway. I might as well make some money." These workers jump to point B and drag up the average output. Safelite's productivity increased dramatically: 44 percent in 6 months. That is great, but, interestingly, only half of the increase was due to the incentive effect. The rest is attributable to the effect of the scheme on the composition of Safelite's workforce.

When people think about instituting a new compensation scheme, they usually do it with their incumbent workforce in mind. That is how it was at Safelite. Halfway through the process, human resources executives approached me with a concern. They said, "You know, we're losing all our workers." My reply was, "Maybe that's exactly what you want." A year later, their new labor force was 24 percent more productive than the old labor force as measured at a comparable career-stage. A person with 2 months service under the new system was, on average, 24 percent more productive than a worker with 2 months service under the old system. Safelite was attracting the more energetic, ambitious employees from their rivals. And most of the selection took place through new hiring, not through turnover. It was not the case that the good people stayed and the bad people left. Turnover was random across the different types of employees. It went up slightly, but not selectively. There was a change in Safelite's applicant pool. The incentive built into the piece-rate system was attracting people who responded to that type of incentive.

Windshield production is a simple process, producing an easily-monitored product of a single standard. It suited the introduction of piece-rates and individual incentives. But how do you provide incentives in a team context?

Incentives & TeamsBritish Petrol & Exploration, BPE, has an oil field in Prudhoe Bay in northern Alaska. It is an unique place with 300 people living and working there. To motivate the workers, BPE introduced a team incentive scheme. It measured monthly output and, based on the team output, provided a monthly bonus. It worked well. After 6 months productivity increased more than 12 percent. BPE was so pleased it tried the same thing at the head office in Anchorage. However, it was a disaster. People hated it; staff quit; it just did not work.

The situations in Anchorage and Prudhoe Bay were very different. In Prudhoe Bay people had to work together, live together, and, at the end of the day, barrack together. It is a small community. If you shirk on the job, the people that are doing the extra work for you are in the position to punish you for it, one way or another. So, even though a team of 300 people is very large, the fact that they are involved with one another on a 24-hour basis creates strong enforcement mechanisms.

The situation was different at Levi Strauss, the clothing company. Levi's is a worker-oriented company. It had good intentions when the piecework system was abandoned in 1992. Under that system, individual workers performed single, specialized tasks and were paid according to the work they completed. Under the new system, groups of 10-35 workers shared tasks and were paid according to the work the group completed. Levi's goals were to alleviate the monotony of the old system, to allow stitchers to do a variety of tasks, and to reduce repetitive stress injuries. What happened?

Well, instead of motivating workers and making them happy, it damaged morale and triggered corrosive infighting. Skilled workers were pitted against slower colleagues. Threats and insults became common. Long-term friendships dissolved. Faster workers tried to banish the slower ones. What the company calls "efficiency", or quantity of pants produced per hour, plunged in 1993 to 77 percent of pre-team levels. In the years after the transition labor and overhead cost raced up 25 percent. It was a disaster. Ultimately Levi's dropped the whole thing.

Why did the team incentive system worked so well in Prudhoe Bay and failed at Levi's? How were these situations different? The answer is producing jeans does not require teamwork. Jean production is more like the production at Safelite; each task is easily performed independent of other workers, and easily monitored. Under this situation, team compensation is a very weak incentive device and can, in fact, dilute incentives. The incentive power of a team incentive scheme is compromised by the fact that individuals can "free ride". Thus, you would be better off to avoid team compensation unless where teamwork is valuable. Use team compensation only when team production is an integral part of the business. This is rare. By and large, people tend to overstate the importance of teams.

The key points are:

(1) For production workers, pay on output is very effective. However, many firms are reluctant to tie compensation to tangible measures of output. Managers find it is harder to compensate people on observable units of output. It is easier to simply pay everybody the same.

(2) Sorting is as important a reason for introducing output pay, as is incentive. At Safelite, much of the increase in productivity was a result of changes in the workforce. Selection tends to be under-emphasized.

(3) Team-based pay is only effective when production is truly a team effort. Often times, team incentives are weak and may cause resentment.

Incentives, Retention, & Retirement

Still on the topic of worker turnover, but in a different context, I recently consulted in the Netherlands, where they have a problem familiar to many countries: early retirement against the background of an aging workforce. People were commonly retiring at age 59. That creates problems, as the younger portion of the workforce has to support these retirees. The Netherlands wanted to induce workers to stay in the labor force longer. The way to do that was through their pension plan.

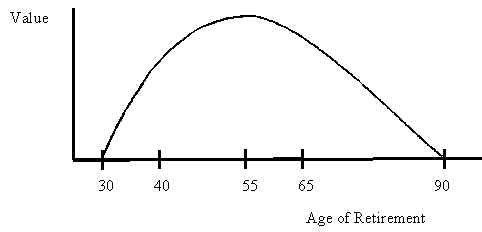

Almost all workers in the Netherlands are covered by what is called a defined benefit pension plan. Under such a plan, your annual pension is calculated as a percentage of your salary - of your final, or perhaps average, salary - multiplied by years of service. The more years of service, the greater your pension. The problem in this design is in its offsetting effect: the more years of service you have, the fewer years you have to enjoy the pension flow. This is a feature of every defined benefit pension plan. Figure 2 displays such a plan's typical inverted-U shape. So, taking an extreme example, let us say a worker started at a firm at age 30 and also left that firm at age 30. The value of his pension would be zero. At the other extreme, the worker stays with the firm until age 90, retires, and dies later that same day. He would receive a huge annual pension, but only get to enjoy it for 2 minutes. The value of that pension is also zero. Thus we get the shape of our graph; if each end is zero and in the middle is positive, then the function has to have an inverted U shape. What does that tell you? It tells you that past a certain age - in this diagram around age 55 - you are giving up money by staying on at work. Certainly, each additional year that you work rewards you with a greater pension benefit, but you will have fewer years to draw on it. Defined benefit pension plans induce this retirement pattern and the steeper the decline, the more early retirement you induce.

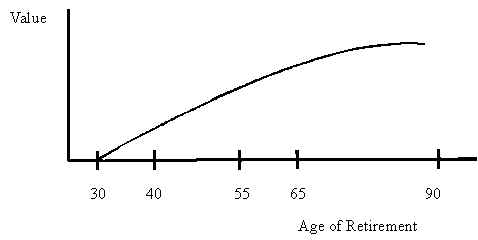

Figure 3 has a different shape. It describes a defined contribution plan. Here, accrual is always positive, at least regarding the expected present value. Of course, your pension may be invested in a market fund that does poorly, in which case, the pension value goes down, but normally, each year you contribute money to the fund so the expected value of the fund continually goes up. When your contribution is defined, it is irrelevant when you retire, because you own the fund. You can take it now, take it later, or bequeath it. It is part of your wealth. In a defined contribution plan you do not have the same incentive to retire that you have with a defined benefit plan.

Of course, defined contributions are not always appropriate. Those of you who have visited us in California will know that Stanford is a very attractive university. A professor there can have a nice life. We are not monitored. Our work is interesting. Why should a professor retire at 70 or 75 years of age when he can just as well stay in his job and draw his salary? My pension plan certainly encourages me to do that; it continues to accrue as long as I stay on in my job. Senior professors at Stanford have no reason to retire. So the university has a problem with late retirement. This is because of their pension plan. To induce early retirement, you need a defined benefit plan in which accrual reduces rapidly with seniority.

Stock Options & Retention

Stock Option is a very popular retention device in the United States and increasingly so in Europe and Asia. In the States, Cisco Systems, for example, gives stock options to every worker in the firm, from top to bottom. The venture capitalists opposed it, but Cisco has been very effective in retaining its workforce. About three years ago a Chinese company, Hua Wei, sought our advice on this same issue.

Hua Wei had a retention problem. They were losing workers to their competitors, so they decided to give options, but then found the workers did not want them. The workers doubted their value. These workers were advised to take the options, but they were relatively low-income workers who could not bear the risk. Options are volatile. If you have to support a family, you do not want options, you want income. This situation demonstrates a vital point about options and retention: options do not, in and of themselves, create retention value. It is the non-vested part of the option that does that.

Cisco retained its workers not because it gave options, but because the options did not vest until after another four years. A company could produce the same effect with some other form of deferred compensation. They could give a bond. Conceptually, Hua Wei could have bought US Treasury bills and put them in an escrow account for every worker. Then, for each year a worker was with them, they could take one-fourth of his Treasury bills vested, and give them to the worker. In 4 years the worker would had vested 100 percent of his T-bills. The company could then put in another set of T-bills and roll it so that it would be 1 to 5 years and then 2 to 6 years and so forth, indefinitely. This would produce the same retention-effect without pushing the risks onto the workers.

So, I want to emphasize this: it is not the options that create retention; it is the non-vested component that creates the retention. Some portion of the compensation should be delayed, and a worker would get that only if he stays. But options are best reserved for high level employees who can significantly affect the value of a firm and can bear the risks involved. In a company like Cisco, there are employees who made millions in options, but for every Cisco, there are many more other companies that went belly-up and their options are worth nothing.

Other Uses For Incentives

The way you structure a compensation package can have broader uses. It can help you elicit information. Here is an example: I taught an executive course in Singapore and one student was the CEO of a small clothing-manufacture company, Bentley Clothing. Bentley made pajamas, T-shirts and low-priced clothing, and are sold almost exclusively in the US through large chainstores like Wal-Mart, K-Mart and JC Penney. This CEO asked my advice about a business proposition. A woman in New York, whom we will call "Sarah", had suggested Bentley starts a line of lingerie, and offered to handle the sub-contracting. Bentley was unsure whether to go with the proposal.

The figures in the offer were as follow: the prospective sub-contractor wanted a 7 percent commission on sales with a guaranteed $140,000 a year. The margin on the new line would be 30 percent. The fixed cost of setting up a new line was about $3 million, so, in the larger picture, Sarah's salary was trivial. Bentley was concerned about putting up so much money in an area where, firstly, it had no expertise, and secondly, it had to rely on the expertise of the proposer, who, under the suggested terms, would have been guaranteed $140,000 a year in salary whether the line was successful or not. Bentley was bearing all the risks.

I put the offer to the class, and, after consideration, they recommended that Bentley not to enter into this deal. Most class-members rejected the proposal because they were suspicious of Sarah's intentions. This raises the point: could we have framed a deal to help us gauge Sarah's commitment? Absolutely. We would ask her to put her money where her mouth is.

Let us say that "Sarah" was the head buyer of a big New York department store. She is making $300,000 a year, so her willingness to accept a base salary of $140,000 proves her commitment to the project. She is giving up $160,000 a year in salary, so she must believe she stands to make at least that much in commission. This is valuable information and you can get that information by simply offering a lower base salary with a higher commission rate. Instead of offering $140,000 a year and starting the 7 percent commission at $2million, you might offer $70,000 a year with 10 percent commission after sales of $7 million. That is what Bentley did. Sarah declined the offer. Her commitment was not that great, and the structure of the compensation scheme elicited that information.

Venture capitalists do this kind of thing all the time. When Steve Wozniak wanted the money to start Apple Computer they made him put up everything from his old Volkswagen to a worn-out sweatshirt. It is trivial as capital or assets, but Wozniak had information about the value of his proposal that the venture capitalists did not have. This was a way of eliciting that information. Is his proposal worthwhile? Is he willing to bet everything he has on it?

Questions & Answers

1. What are your views on big differentials between senior and junior pay?

Usually, the problem is not that pay differentials from the top to the bottom are too big, but rather, too compressed. Too much pay compression creates adverse selection. If the good people get only slightly more than the not so good, who is overpaid? You then get selective turnover working against you. The good people tend to leave and the bad people tend to stay. Firms with compressed salary structures tend to lose their better people. Firms that have dispersed salary structures tend to keep their better people.

There is a trade-off, of course. A very dispersed salary structure can undermine some of the cooperative spirit of the firm. Big pay compensation can make people very competitive. That could detract from a cooperative environment. It is a team issue. If team production is very important to your firm, you will tolerate a little more pay compression.

2. What is the incentive-value of stock options in times of fluctuating markets?

A stock option always contains a tension between current and future incentives. Suppose the exercise price of an option is set at 100, but the market falls and stock price drops to 60. The employee did not cause the market to fall, but it is the employee who bears the cost of it. He is $40 down and who knows when the stock will get back to $100? This could have a disincentive effect.

One solution is indexing, but that is unpopular, in part because you do not know what a good index is. The index might be very noisy; people think they could be manipulated. The standard approach is to make a kind of an ad hoc index, simply re-pricing the shares. It is a common practice to re-price options. The market falls, so you re-set the exercise price from $100 to $60. Re-pricing the options reinstates the incentive, but should you re-price the options every time your stocks fall? That would destroy the incentive, because it insures the stock against any variation. But, some re-pricing is warranted, and it would be possible to work out an optimal re-pricing structure, somewhere between 100 percent re-pricing and 0 percent re-pricing. They index in Mexico, but they are accustomed to indexing against chronic high inflation. Many compensation consultants have argued for it in the US, but nobody wants to do it.

3. Is merit pay a good incentive in the context of teacher motivation?

In the field of education, pay is less an incentive issue and more a sorting issue. In the United States, the SAT scores of the average public school teacher, when in college, placed him or her on the 35th percentile in Math and the 44th percentile in Verbal. That means the average teacher was drawn from the lower half of the distribution. Changing to merit pay will not affect those people who are already out there in the field, but by paying more you could change the kind of people you attract, as Safelite did. You would attract those people who would be better teachers and lose those people who would be poorer teachers. This relates to the point about pay compression. If you spread out the compensation structure, you will attract the better people and get rid of some of the poorer ones.

Eric Hanushek, of the University of Rochester, has done a lot of research on the effects of various factors on educational output. He has found that all that matters is teacher-quality. Put kids in a good teacher's class, they do well. Put them in a poor teacher's class, they do poorly. Teacher- quality matters. If you pay more, you get the ability to select from a larger pool of applicants. You get better-qualified people.

4. What effect does options has on "shareholder value"?

Compensation mechanisms, retention strategies, all this is supposedly for the benefit of shareholders, but granting large pools of options can destroy, or at least fail-to-maximise shareholders' value, and even sophisticated business people sometimes seem to forget that options are real money. Options cost the company money. You can offer your workers lower-based salaries and ask them to take the difference in options, in effect, asking them to finance the company. But are they the best people to do that? Are they offering the lowest-cost financing? Furthermore, giving options can reduce your diversification because it overlaps your human and physical capital. Options are best applied at the top of the organisation. Use deferred compensation and more direct forms of compensation at the bottom of the organisation.

This article is based on the transcript of a lunch talk given by Professor Edward P. Lazear on March 9, 2000. Professor Edward Lazear, a senior fellow at the Hoover Institution since 1985, is also the Jack Steele Parker Professor of Human Resources, Management and Economics (1995) at Stanford University's Graduate School of Business, where he has taught since 1992. Professor Lazear was the first Vice President and is now the President of the Society of Labour Economist.

Figure 1

Figure 2

Expected Present Value of Defined Benefit Pension Plan

Figure 3

Expected Present Value of Defined Contribution Pension Plan